This post may contain affiliate links. Please see our disclosure policy.

Canning milk is gaining popularity in “rebel canning” groups, but is the process safe? I’ll walk you through the pros and cons of canning milk at home, including recipes for canning milk currently circulating on the internet.

There are no safe tested recipes for canning milk at home from the USDA or National Center for Food Preservation, and I’ll explain why. There are good reasons why milk is canned commercially and not at home, and there are good reasons why people can milk all the time without getting sick.

I’ll explain it all, and let you make your own informed decision.

How do you can milk at home?

That’s a question I get a lot from my readers, and time and again, I respond to emails asking just that. Just this morning, a reader asked,

“Our question is about home pressure canning milk. It is debated on whether it is safe to can dairy in most blogs I read. Some say they’ve been doing it for years, and others say no way. It’s hard to believe that large companies can process milk safely, but it’s not safe at home. Please tell us your experience/thoughts on home canning dairy?”

Every time I get this question, I type a long and detailed answer, and I think it’s about time I explain the pros and cons of canning milk at home for everyone.

Personally, I do not can milk at home.

We are home cheesemakers, and I put away pound after pound of raw milk cheddar, Colby cheese, and dozens of other cheesemaking recipes each year. For fresh milk, freeze-drying milk is my standby because it rehydrates back to EXACTLY the same as fresh milk with no cooked taste, and it’s not grainy like commercially dehydrated milk.

That said, cheesemaking has a long learning curve, and not everyone has a freeze-dryer at home. So why not try pressure-canning milk?

Well, there are plenty of good reasons (beyond the fact that there is no scientifically tested method for canning milk at home), but I’ll let you make the decision for yourself.

How is Milk Canned Commercially?

If you’re hoping to can milk at home as it’s canned commercially, you should probably start by understanding how evaporated milk is made and canned commercially.

A quick look at Wikipedia gives you a basic answer that’s enough for most people, and is correct for most situations if you’re just generically trying to understand what’s going on, rather than recreate it at home:

Per Wikipedia:

“Evaporated milk is made from fresh, homogenized milk from which 60% of the water has been removed. After the water has been removed, the product is chilled, stabilized, sterilized, and packaged. It is commercially sterilized at 240–245 °F (115–118 °C) for 15 minutes. A slightly caramelized flavor results from the high heat process (Maillard reaction), and it is slightly darker in color than fresh milk. The evaporation process concentrates the nutrients and the food energy (kcal); unreconstituted evaporated milk contains more nutrients and calories than fresh milk per unit volume.”

There’s an industrial food science textbook titled A Complete Course in Canning and Related Processes, which walks you through the commercial canning process for milk (and just about everything else, from soup to spaghetti-os). It has a really comprehensive chapter on how milk is canned in a commercial cannery, and most of the content centers around how it’s first filtered, standardized, homogenized, and otherwise made identical to all other canned milk so that the processing time and temperatures are the same for any given batch.

Eventually, once they make it to the canning process, it says, “The sterilization time-temperature regimen of evaporated milk ranges from 110 to 120 degrees C (230 to 248 F) at 15 to 20 minutes duration.”

It follows up with instructions for making UHT milk, which is shelf-stable milk in aseptic packaging that’s often sold in places without access to refrigeration. It’s not evaporated milk, and it tastes much more like regular milk (though it still has a cooked flavor). Making UHT milk “requires ultra-high temperature (UHT) sterilization prior to packaging, known as flow sterilization (a continuous process). The sterilization temperature is controlled at 130 to 140 degrees C (266 to 284 F) for a few seconds, and then the sterilized milk goes through the filling and sealing processes under aseptic conditions.”

Making UHT milk requires a lot of specialized equipment, ultra-high temperatures (and then rapid cooling), and really just can’t be achieved in canning jars at home. Heating to very high temps like that won’t work in glass jars, and that’s hotter than a home canner can safely achieve. Even if you did have a canner that could do it, you can’t flash heat and cool glass jars like that.

That said, the process for canning evaporated milk in cans basically uses common pressure canning technology, including processing times and temperatures that can be achieved in a home canner. The variation in time/temperature depends on the fat content and milk solids in the batch, as different manufacturers and different countries have different standards for evaporated milk. (For example, in the US, evaporated milk must be at least 6.5% milk fat and 23% total milk solids, but in Canada, evaporated milk must be at least 7.5% milk fat and at least 25% milk solids.)

Keep in mind, that cow milk naturally varies in composition based on the season and the breed of cow, and Jersey cow milk is already around 5% milkfat in the spring (without being concentrated into evaporated milk). Often, home-raised milk is of higher quality, with more nutrition and milk solids than what they’re getting industrially from feedlots.

Assuming you’re canning regular milk, it’d be thinner than the concentrated evaporated milk with 60% of the water removed that’s being put up commercially, so it’s not going to be more concentrated than the factory stuff (but it might be close if depending on breed and season). For safety, using the highest processing temperature and time makes sense, given you don’t have a rigorously standardized product as they do in the factory. And, it’d be better to can it without concentrating it into “evaporated” milk.

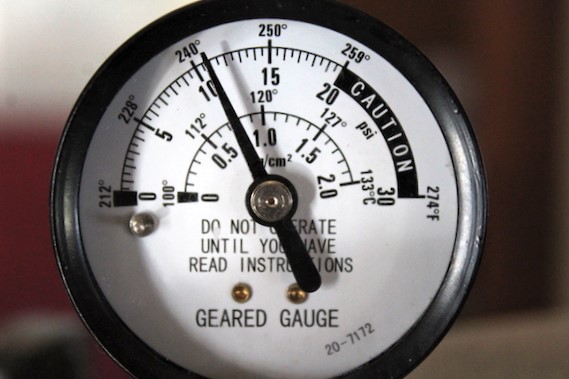

In a home pressure canner, that’d roughly correspond to the following times and pressures (below 1,000 feet in elevation):

- Lowest Time/Temps: 10 Pounds Pressure, Maintained for 15 minutes

- Highest Time/Temps: 15 Pounds Pressure, Maintained for 20 minutes

(Keep in mind, if you’re above 1,000 feet in elevation, it would be hard to hit the appropriate pressure for adequate processing, as most canners top out at 15 pounds of pressure.)

That, at least, is how canning milk works commercially.

What’s Wrong with Canning Milk at Home?

So, what’s different about canning milk at home vs canning milk commercially?

There are a few things at play here. First, home-harvested milk isn’t rigorously standardized, and it varies dramatically in fat, protein, and milk solid contents. Many backyard homesteaders are raising dairy goats instead of cows, which alters the chemistry as well. But still, when not concentrated, it should still be able to be processed in a similar way to how milk is processed commercially.

The main problem is, when you see instructions for canning milk online, they’re not doing anything close to what it looks like commercially. They’re basically just heating the milk enough to cause the jars to vacuum seal, which isn’t anywhere near hot enough to kill off botulism spores or other similar contaminants. (I’ll go over those commonly circulated instructions shortly.)

Luckily, those contaminants are rare, so you can actually can milk like this pretty successfully, for years even, without an issue…until your luck runs out. While botulism spores are harmless in the open air, place them in a sealed anaerobic environment inside a canning jar, and they proliferate and produce botulism toxin, which is deadly.

A single botulism spore in the wrong place could multiply and be catastrophic. That said, botulism spores in milk are pretty rare, as they’re often soil-born contaminants, and they’re more likely to be found on things like potatoes, onions, and garlic. Still, cows are out in the dirt…and it does happen.

But, that is why someone can process milk at home using insufficient processing for years, or even a lifetime without issue. But it’s like Russian roulette and bad luck on a single batch can be fatal.

So why are people under-processing milk?

The reason is that when you actually process milk at high temperatures, it really changes the taste, and the natural sugars in milk carmelize and taste nothing like regular milk. This happens even when milk is boiled, but it’s extreme if you’re getting it up to 15 pounds pressure.

Most people find this type of milk unpalatable, so that’s why people are under-processing milk at home. Few people are drinking commercially processed evaporated milk right out of the can, and that stuff is filtered and treated with stabilizers and other additives to help it survive the high-heat process.

If you put regular grocery store milk in a canning jar (or home-harvested raw milk) and actually canned it at 15 pounds pressure for 20 minutes, it’s kinda nasty and really not worth drinking. It’s so intense that it makes baked goods taste off as well.

It’s not worth doing, so the National Center for Food Preservation in the US hasn’t developed guidelines for it. Why would you put many thousands of dollars of research money into testing something that makes an unpalatable product?

Rebel Canner Instructions for Canning Milk

So what are people doing when they say they’re canning milk successfully at home?

The most commonly circulated recipe for canning milk at home comes from the Rebel Canners Cookbook by Tammy McNeill.

Most of the recipes in the book are actually safe canning recipes, believe it or not, and most do follow USDA guidelines (even though it’s labeled a rebel cookbook). In most places, there is a lot of leeway in changing canning recipes; it’s just that few people know the rules, and there’s a lot of fear about changing things (even when there are quite a few published guidelines when it comes to designing your own canning recipes).

Anyhow, though many of the recipes in the book do follow common canning guidelines, quite a few of them are true “rebel canning” recipes, and her canning milk recipe is one of them.

The author, Tammy McNeill, is the leader of the popular online Facebook group called Rebel Canners, and her method is by far the most commonly recommended on the internet. She suggests the following:

“I canned milk two years ago about 45 pints. I am still using them. The process I used is simple. Put milk in pints. Bring up to 5 pounds of pressure. Turn the canner off and let cool completely before opening it. The usual pressure for my altitude is 10 pounds of pressure, but milk is done at 5 pounds of pressure at my altitude. It is one of the few exceptions to the ’10-pound rule.’ I only use this in cooking as the milk sugars carmelize, and the flavor changes slightly to a sweeter product. The milk fats will separate so shake before opening. This caramelization makes it really good in hot cocoa.”

The recipe is a bit vague, but we’re going to assume that she hot packs the jars by bringing the milk to a boil in a separate pan before filling the jars. There’s no headspace listed, but I’ve seen 1 ” as a headspace for canning milk, which is often used when canned goods have a lot of fat present (such as with meat or meat broth).

I’ve also seen 1/2 inch as a canning headspace for milk, simply because the jars seal more dependably with this really short processing time. (Improper headspace will impact your sealing rate, and this really short canning time might not be enough to seal a jar with a 1” headspace properly.)

So what she’s doing here is simply bringing the canner to 5 pounds pressure (which is 228 F at sea level) and then allowing it to cool. There’s no “processing time” and in truth, the canner is hitting 228 F, but the contents of the jars are not. It takes a while for that heat to penetrate all the way into the jars.

I’d guess the jars are hitting slightly above boiling at an internal temperature, but nowhere near 228 F. And obviously, nowhere near the commercial guidelines of “230 to 248 F for 15 to 20 minutes duration.”

The jars will vacuum seal, and organisms like lactobacillus and mold will be killed…but botulism isn’t killed until at least 240 F, and it loves the anaerobic environment inside of that canning jar. Luckily, as I said, botulism spores need to be present to proliferate, and most of the time, they’re just not.

So you can, in fact, get lucky for years and can milk using this process, potentially even for a lifetime without any ill effect.

Or you could get really unlucky the very first time.

The other thing that’s happening here is kinda tricky. Even heated to a low temperature, the milk in those jars still changes in flavor, and it’s still a bit “off” for just drinking, as Tammy says. She mostly uses it for baking.

That’s actually kinda convenient, given that botulism is denatured by cooking. You can look this up on any reputable canning source, including the USDA.

If a jar is at all suspect, they recommend throwing it out, of course, but the USDA also mentions that,

“If it is possible that any deviation from the USDA-endorsed methods occurred, to prevent the risk of botulism, low-acid…foods should be boiled in a saucepan before consuming even if you detect no signs of spoilage. At altitudes below 1,000 ft, boil foods for 10 minutes. Add an additional minute of boiling time for each additional 1,000 ft elevation. However, this is not intended to serve as a recommendation for consuming foods known to be significantly underprocessed according to current standards and recommended methods. It is not a guarantee that all possible defects and hazards with non-recommended methods can be overcome by this boiling process.”

According to the World Health Organization, that’s more than is strictly required: “Though spores of C. botulinum are heat-resistant, the toxin produced by bacteria growing out of the spores under anaerobic conditions is destroyed by boiling (for example, at an internal temperature greater than 85 °C for 5 minutes or longer).“

A temperature of 85 C corresponds to about 185 F, or barely simmering. Simply reheating the food before eating it is often enough to destroy botulism if it is present in the jar, and if Tammy is using it in cooking, or even just hot chocolate, rather than drinking it right out of the jar…honestly, that’s probably enough.

So a combination of luck, and the fact that home canned milk is usually re-cooked is why your granny has canned milk at home using this low temp method for 50+ years, and no one’s gotten sick.

Still, it’s not something I’m doing or something I think is worthwhile to put on my shelf.

Is Canning Milk Safe?

Canning milk at home is not currently recommended by the USDA or National Center for Food Preservation. The main reason for this is that when milk is properly processed at home, the resulting product is mostly unpalatable (10 to 15 pounds pressure for 15 to 20 minutes).

In a commercial setting, they filter out milk sugars, adding stabilizers and more, which helps factory-made canned milk stay mostly palatable, but even then, it’s mostly used for baking.

When milk is “processed” at home using the commonly circulated rebel canning instructions, it’s not adequately processed to prevent botulism, and it is not safe to drink right out of the jar (bring to 5 pounds pressure, then turn off the heat).

That’s more or less what makes a canning recipe “safe,” that the food isn’t developing toxins in the jar on the pantry shelf, and that no additional processing is needed to render it safe before eating.

Just because someone you know has been lucky and has been canning milk for a long time with no ill effects doesn’t mean it’s a dependable product or that the canning process used makes it free of pathogens or contaminants.

Foods that need to be re-boiled or cooked out of the jar before eating are not generally considered “safe” canned goods, as they could have toxins present that could make someone sick. The main idea of canning is proper sterilization, and most people will assume that if it’s shelf stable in the jar, they can just eat it off the shelf (without having to sterilize it again).

Some rebel canners do add the caveat that home canned milk needs to be re-cooked for at least 10 minutes before consuming, but when that condition is added, recipes are not considered “safe canning recipes,” as skipping that extra step could be disastrous.

I do not recommend canning milk at home, and I believe there are many other better, timer-honored ways of preserving milk. Canning seems like a traditional “old-time” preservation method, but it really has only been around for the past 100 or so years, and much of that history is spotty when it comes to food safety.

Many early canning recommendations from 50 to 100 years ago are no longer considered safe, and for good reason.

Just because something will go into a jar, doesn’t mean it’s necessarily a good idea.

That said, my goal here is to give you enough information to make an informed decision on the topic for yourself.

What about powdered milk? Has it been processed enough to add to pressure canned products safely?

No, unfortunately not. It’s dried to make it shelf stable, but it’s not any more sterile than normal milk. It’s not the bacteria that you’re worrying about anyway, it’s that milk is very basic (in terms of pH) and it’s denser than water, and the lower pH and higher density impact how heat moves through a jar. That isn’t any different (or if anything, worse if you don’t rehydrate it) than normal milk and shouldn’t be used.

This was a concise but complete discussion that answered many of my questions, not just about milk but pressure canning in general. Thanks!

You’re quite welcome!

Thank you for this. It provides a lot of clarifying info for us newbs who are trying to filter through all the varying opinions vs science.

You’re quite welcome!

In 2018, the most recent data I could find. There were 17 cases of food borne botulism in the entire population of the United States, a third of a billion people. None of them were fatal.

93 percent of botulism cases are not food related.

Maybe continuing to hold the boogey man of botulism as a standard for food safety is unreasonable.

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6429a6.htm

This happened in Ohio in 2015 one person died. From canned potatoes made into potato salad at pot luck.

Not sure if you were looking at deaths closer to 2024.

Thank you for the information.

I agree with you.